@johncarlosbaez typo? 65/45 -> 64/45 😬

@johncarlosbaez A very interesting post with a long thread of comments

https://mathstodon.xyz/@johncarlosbaez/115774416563837297

@johncarlosbaez Holy shit. This information is EXACTLY what I needed right NOW! Thank you John!

@rtn - thanks, that's great! You might like my blog articles about this stuff... or maybe it's too much.

For more on Pythagorean tuning, read this series:

https://johncarlosbaez.wordpress.com/2023/10/07/pythagorean-tuning/

For more on just intonation, read this series:

https://johncarlosbaez.wordpress.com/2023/10/30/just-intonation-part-1

For more on quarter-comma meantone tuning, read this series:

https://johncarlosbaez.wordpress.com/2023/12/13/quarter-comma-meantone-part-1/"

For more on equal temperament, read these:

https://johncarlosbaez.wordpress.com/2023/10/13/perfect-fifths-in-equal-tempered-scales/

Hi! A couple of thoughts from someone who is fascinated with musical tuning but in a fairly superficial way.

First, in looking at the hexagonal grid pages about 2/3 of the way through I wondered: You touch on scales with more than 12 tones, but only in the guise of equal temperament (29-TET). Would it be possible instead to develop a family of "just" intonations with 29 tones? Would it be described by a similar kind of grid, just with more elements, or would the shape be different?

Second, I went looking in OEIS for the list of "best approximation to 3/2" and found https://oeis.org/search?q=5%2c7%2c12%2c29%20id:A060528 -- but it goes 1,2,3,5,7,12,29,... and I can't figure out what difference between the two statements of the problem leads to 3 being/not being on the frontier of best approximations.

Finally, just an observation: It's unusual to see a discussion of tuning without an appeal to the overtone series somewhere. I assume this was a conscious decision.

@stylus - people do indeed develop just intonation scales that are more complex than the historically important one I explain.

In Pythagorean tuning, all the frequency ratios are of the form

2ᵃ 3ᵇ

so this is also called 3-limit tuning.

In the just intonation I explain, they're all of the form

2ᵃ 3ᵇ 5ᶜ

This is 5-limit tuning.

People have gone on to study 7-limit tuning, 11-limit tuning, etc.

You're making me wonder if one of these, preferably involving not too many of these, could fit well with a 29-note scale. Maybe, as you suggest, 5-limit tuning or even 3-limit tuning could do the job!

This is a great math question, and I haven't seen anyone discuss it. But I've mainly been interested in the historically widely used systems. To explore the wild universe of mathematically possible systems, this is a good resource:

https://en.xen.wiki/w/Main_Page

Maybe the answer to your question is lurking in there.

"Finally, just an observation: It's unusual to see a discussion of tuning without an appeal to the overtone series somewhere. I assume this was a conscious decision."

Yes: my talk will be just 50 minutes long. After a run-through of basic harmony concepts to get the non-musical mathematicians in my audience up to speed, I think I'll just barely have time to explain Pythagorean tuning and just intonation. I want to explain them slowly and clearly enough so it sticks.

If I had two hours I could say a bit about *why* rational numbers are a big deal (this is more physics than math), and also delve into the wonderful world of quarter-comma meantone:

https://johncarlosbaez.wordpress.com/2023/12/13/quarter-comma-meantone-part-1/

I like to think someday I'll write a short book about this stuff.

@johncarlosbaez i do NOT understand math or music, but still enjoyed reading all of this. Thanks :D

@timitii - glad you liked it!

@johncarlosbaez Hey that's great. I don't know the first thing about music theory. But one of the kids is learning an instrument and I've got a math background... This is very welcome, thanks! And happy holidays.

@hambier - great! Hope you and your kid enjoy it.

@johncarlosbaez For people curious about the subject, I want to mention the lovely 2023 ICFP FARM talk by Gloria Cheng https://youtu.be/k_htPyDDIwk?si=TpvGiQL1Nq-dE4Kl

[FARM'23] Keynote: Perfectly Imperfect: Music, Math and the Keyboard

YouTube

@johncarlosbaez Would love to see the video recording of the talk, if any.

@johncarlosbaez That's really good! Thanks!

@johncarlosbaez

Wow! Thanks for this, it's fascinating!

I'm sure you're well aware of all those other notes there are, that appear in, for example, Ottoman scales, Indian music, and so on...

@johncarlosbaez i like this web page https://aatishb.com/dissonance/ and this video https://youtu.be/tCsl6ZcY9ag which explain how harmony and dissonance are related to the overtones of notes

especially because that helps to explain how different tuning systems arise in other musical traditions: western instruments make sounds wih overtones on the harmonic series, but that isn’t true for bells or bars

The Physics Of Dissonance

YouTube

@johncarlosbaez (Typo in first post...missing the 'h' in 'http' for the slides link.)

@johncarlosbaez Recently got curious about temperaments - long story related to Rob Reiner and "This Is Spinal Tap". Found some fascinating information including a standard for defining tunings called Scala - see https://huygens-fokker.org/scala/ if curious.

But not Tmas?

The world is, after all, Minkowskian. That 4th time-like tree is essential, because otherwise how will you know when it's the holidays?

@johncarlosbaez I was expecting to see the 12th root of 2 somewhere in there.

@mocm - patience, patience! If I were giving this talk out loud, I've given the first minute so far.

@johncarlosbaez Math, music and time travel - nice!

@johncarlosbaez One if my favorite topics. The impossibility of a "perfect" tuning has always fascinated me. Kind of like Gödel for musicians :)

If you look at a piano keyboard you'll see groups of 2 black notes alternating with groups of 3. So the pattern repeats after 5 black notes, but if you count you'll see there are also 7 white notes in this repetitive pattern. So: the pattern repeats each 12 notes.

Some people who never play the piano claim it would be easier if had all white keys, or simply white alternating with black. But in fact the pattern makes it easier to keep track of where you are - and it's not arbitrary, it's musically significant.

(2/n)

@johncarlosbaez

As a guy who went out of his way to create a Chromatic keyboard, I can tell you definitively, its easier to play improvised music, and with landmarks provided by blue tape in my case, but could be colors or textures, I dont think it'd be harder to play written.

On the chromatic keyboard, a major key always looks the same, its 3 successive notes from one row followed by 4 from the opposite row. This symmetry makes everything incredibly easier.

88 keys on a grand piano keyboard.

88 constellations recognised by the IAU.

Coincidence?

Yeah... probably... unless there's some additional meaning to the phrase "music of the spheres"...

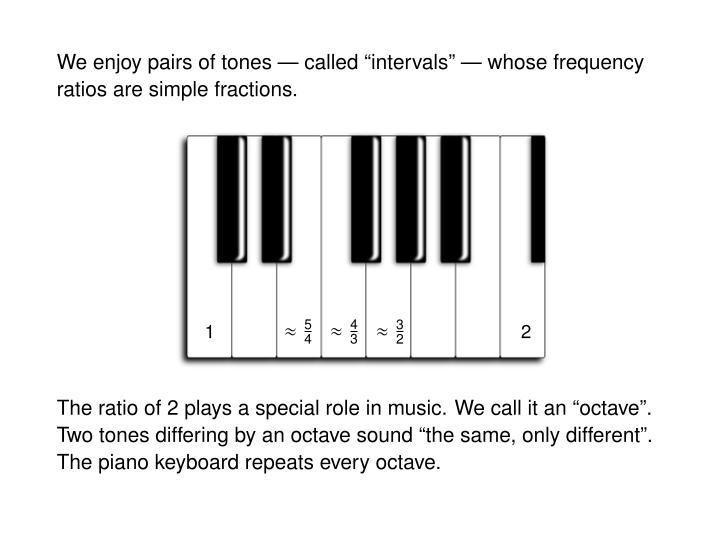

Starting at any note and going up 12 notes, we reach a note whose frequency is almost exactly double the one we started with. Other spacings correspond to other frequency ratios.

I don't want to overwhelm you with numbers. So I'm only showing you a few of the simplest and most important ratios. These are really worth remembering.

(3/ n)

@johncarlosbaez hey, really nice talk, so far! Just a small suggestion: I think it's worth spending some time explaining where those frequency ratios come from. Basically, how the harmonic series expands into infinity and all the notes we are used to are transpositions of the harmonics of C/Do. E.g. the octave is just n=2, the 5th n=3 and so on... As someone else also mentions in the comments, explaining the log nature of frequency perception is important in order to build that mathematical understanding.

@ubik - Alas, I won't have time to explain where the importance of frequency ratios comes from in my one-hour talk.... since my goal is to delve into the math of what you can *do* with those ratios.

But I hope someone in my audience of mathematicians asks about this. Psychophysically it's really about how the overtone series of one note interacts with that of another. So this guy was able to create a timbre that sounds dissonant at an interval of an octave!

Can Octave Sound Dissonant?

YouTube

@johncarlosbaez Why only "almost" exactly double? I know that most intervals on the piano aren't perfect, but I thought that octaves were.

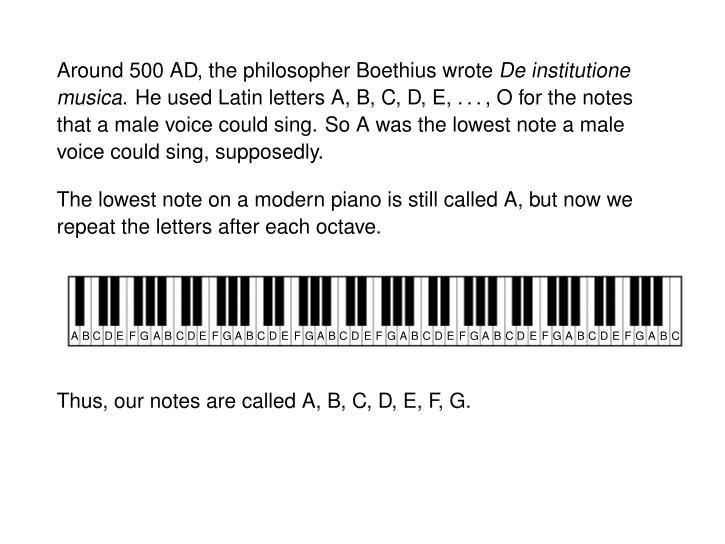

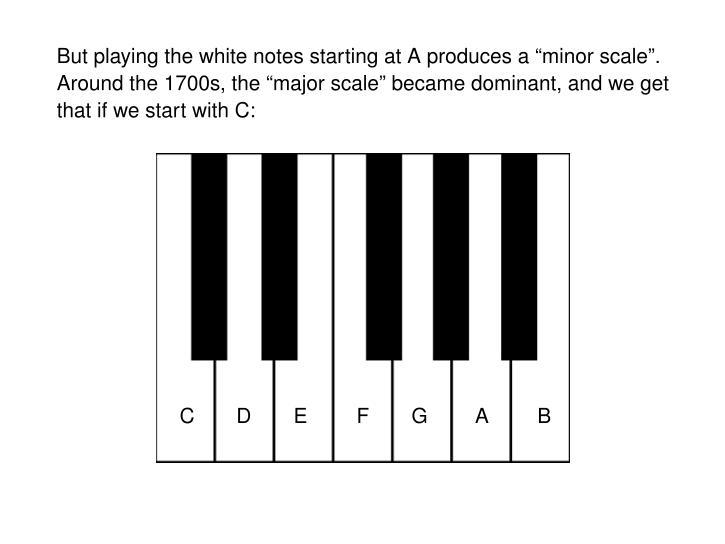

We give the notes letter names. This goes back at least to Boethius, the guy famous for writing The Consolations of Philosophy before he was tortured and killed at the order of Theodoric the Great. (Yeah, "Great".) Boethius was a counselor to Theodoric, but he really would have done better to stay out of politics - he was quite good at math and music theory.

Boethius may be the reason the lowest note on the piano is called A. We now repeat the names of the white notes as shown in the picture: seven white notes A,B,C,D,E,F,G and then it repeats.

[Whoop, Lisa is making me get up, make breakfast and go to the gym. I'll continue this later.]

(4/n)

@johncarlosbaez writes "We give the notes letter names. [...] A,B,C,D,E,F,G"

Thanks for the nice thread.

I think I've already said this here a few years ago. I find it very difficult to get used to use "A,B,C,D,E,F,G" automatically without thinking. I grew up playing musical instruments with "do, re, mi, fa, sol, la, si" corresponding to "C,D,E,F,G,A,B".

Question. I know the origins of the two notational systems. But why does one start with "A/la" and the other with "do/C"?

You kind of mention this in (5/n).

But when did this actually occur?

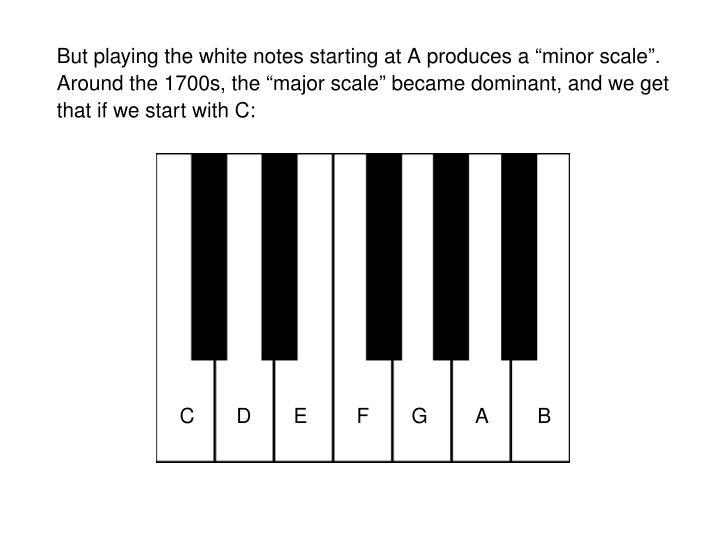

@MartinEscardo - in 5/n, I think I answered all your questions. The popularity of the Aeolian mode (now called the "minor scale") waned, and by very very roughly the early 1700s the Ionian mode (now called the "major scale") became dominant. A easy way to accommodate this shift was to start the scale on C rather than A.

(They could have also renamed C "A" at this point, but presumably that would have been incredibly confusing, especially since the shift took about a century.)

@MartinEscardo @johncarlosbaez And then in German we refer to the note called *B* in English by the letter *H* 🥲

In the picture, you say that Boethius used the letters A through O for the notes that a theoretical male singer could sing. Since I and J were not distinguished in his time, this is 14 letters, making two octaves. Since he didn't repeat letters, it seems strange to stop at the high G and not continue with an extra high A to finish off the scale, but perhaps he thought of scales differently (or just did not have faith in his male singers).

@TobyBartels - interesting. There's always this tension in music between whether you end where you started or just before, e.g. 1 through 7 (the "heptatonic scale") versus 1 through 8 (the "octave"). Maybe Boethius was a 1 through 7 guy.

(In theory there's also the option of 0 through 7, but I guess Western music notation solidified before zero was fully accepted.)

So the scale used to start at A, using only white notes. But due to the irregular spacing of white notes, a scale of all white notes sounds different depending on where you start. Starting at A gives you the "minor scale" or "Aeolian mode", which sounds kinda sad. Now we often start at C, since that gives us the scale most people like best: the "major" scale.

(Good musicians start wherever they want, and get different sounds that way. But "C major" is like the vanilla ice cream of scales - now. It wasn't always this way.)

(5/n)

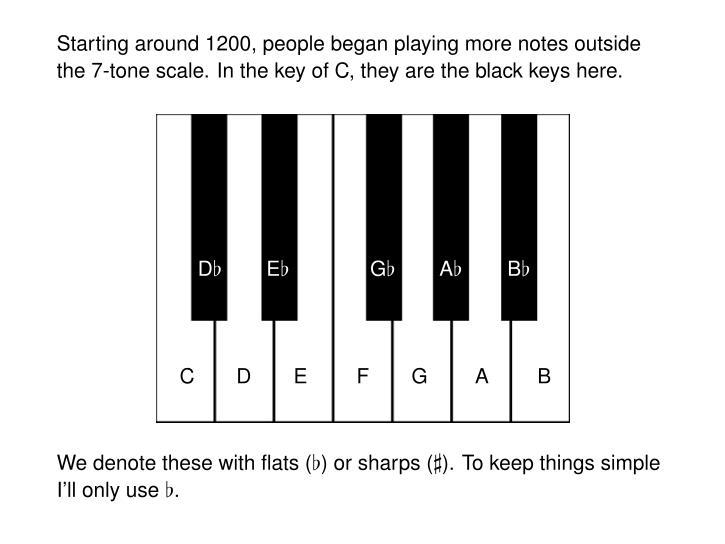

From the late 1100s to about 1600 people called describe pitches that lie outside 7-tone system "musica ficta" ("false" or "fictitious") notes. But gradually these notes - the black keys on the piano if you're playing in C major - became more accepted.

To keep things simple for mathematicians, I'll usually denote these with the "flat" symbol, ♭. For example, G♭ is the black note one down from the white note G.

(Musicians really need both flats and sharps, and they'd also call G♭ something else: F♯. I'll actually need both G♭ and F♯ at some points in this talk!)

(6/n)

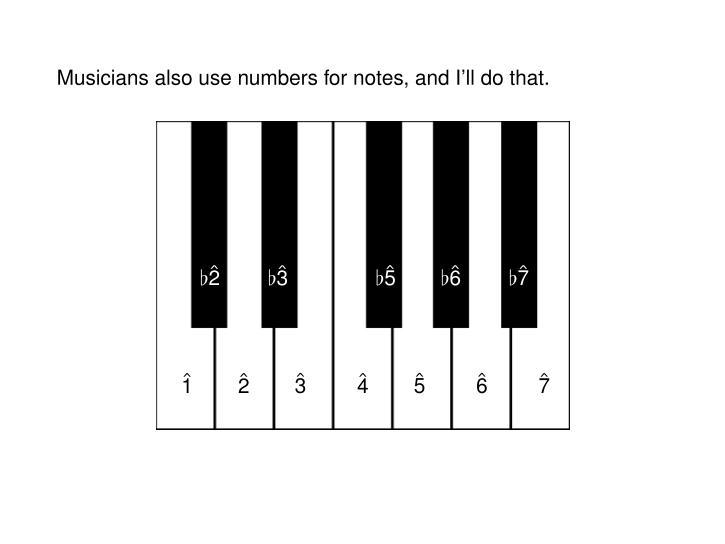

Since starting the scale with the letter C takes a little practice, I'll do it a different way that mathematicians may like better. I'll start with 1 and count up. Musicians put little hats on these numbers, and I'll do that.

For example, we'll call the fifth white note up the scale the "fifth" and write it as a 5 with a little hat.

(7/n)

@johncarlosbaez G# always sounds so tasty to me!

I was pickled by curiosity because in Spanish, and other Romance languages, the notes have other names (Do, Re, Mí, Fa, Sol, La , Si). I found they were introduced for singing training using the Hymn to St. John the Baptist, "Ut queant laxis". They were the first syllables of the verses (except Ut and Sa which were changed to Do and Si for being easier to uterate).

We name the singing training "solfeo".

Nothing to do with math, sorry for the diversion, thank you for the post.

We use those names in English as well, except with Ti instead of Si. (If you know your English-language musicals, then you may have heard them used in The Sound of Music.) But the difference between these and the letters is that the letter notes are at (or at least near) specific frequencies, while solfege (as we call it) is relative. That is, A is always about 440 Hz (modulo a power of 2), but La could be anywhere (with the others arranged at the same relative frequencies).

@edgarchavez @johncarlosbaez in Hindustani classical, the notes are {sa, re, ga, ma, pa, dha, ni} and the alphabet is called "sargam", for the first 4 names

bonfire.mavnn.eu

News and community around mavnn.eu projects.